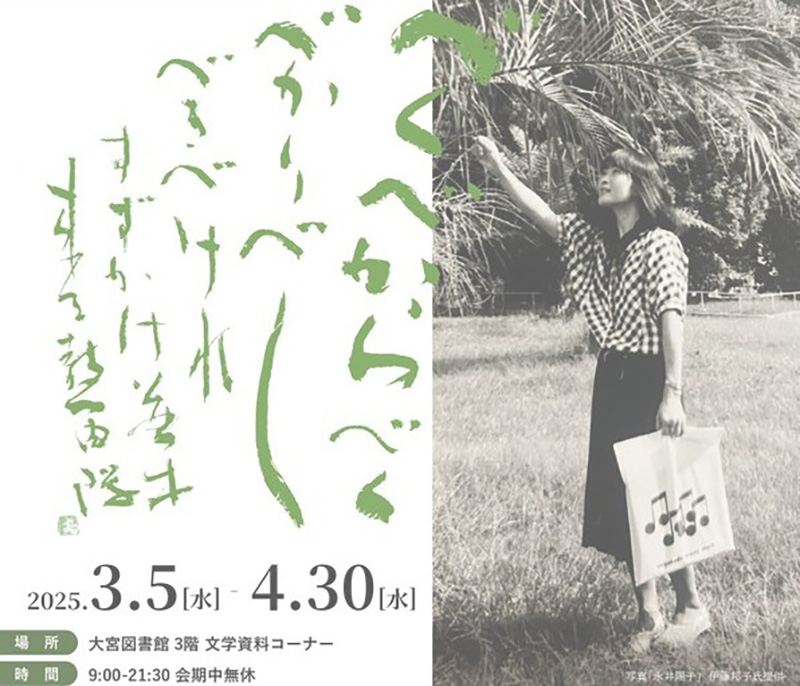

“Yoko Nagai Again – 25 Years After Her Death” from the Omiya Library website

The sunflower of Andalusia is so far away, so far away, but the sunflower of Andalusia is

(Japanese Pronunciation ; Himahari-no andarusia-ha tohokeredo tohokeredo himahari-no andarrusia)

Yoko Nagai “Mozart’s Telephone Directory”

Yoko Nagai is immensely popular among Tanka poets and general readers alike, yet for some reason all of her poetry and essay collections available as new books are out of print. Two poetry collections by Yoko Nagai, “Collection # ‘Mozart’s Telephone Directory’ and Others” and “Collection ♭ ‘Temari Uta’ and Others,” have been published as part of the Tanka Kenkyu Library, edited by Ishikawa Mina. This makes it relatively easy to get to know the whole picture of Nagai’s Tanka poetry. I hope that her only posthumous prose collection, “Momotaro Doesn’t Cry,” will also be published in paperback. This issue features a special feature commemorating the publication of the paperback edition of “Nagai Yoko’s Tanka Poetry Collection.”

Yoko Nagai was born in Shiroyashikicho, Seto City, Aichi Prefecture in 1951 and passed away in 2001. She was 48 years old. She published seven collections of Tanka poems during her lifetime, and a posthumous collection, “I Want a Small Violin,” was published after her death. Her first collection, “Ashi-ga,” was published in 1973, and her seventh collection, “Temari Uta,” was published in 1995, so she published a collection of Tanka poems about every three years. She was a very prolific poet.

I think Nagai’s Tanka can be criticized from various perspectives. However, one thing is absolutely certain: Nagai is a poet who will remain in the history of Tanka for her single poem, “The sunflower of Andalusia”. What’s more, “The sunflower of Andalusia” is one of the greatest masterpieces of postwar twentieth-century Tanka. It’s not just one of Nagai’s representative Tanka poem, but it’s also one of the most representative poem of modern Tanka.

It sounds the same to anyone who reads it, the meaning of “The sunflower of Andalusia” is incredibly simple. It only conveys the meaning that “The land of Andalusia, Spain, where sunflowers bloom, feels far away.” Despite this, most people realize it is a masterpiece the moment they read it. Andalusia is famous for its sunflower fields, but that is irrelevant. It is hard to imagine that the writer was seriously longing for Andalusian sunflowers. However, the reader instantly understands that this Tanka poem is about a longing for something that cannot be attained.

In a sense it could be said to be a demented poem but there is a similar Hiku poem.

Late afternoon, Japanese bindweed flower is visible – Portugal

(Japanese Pronunciation ; Hirugao no mieru hirusugi porutogaru)

Ikuya Kato

The meaning of this Haiku is also shockingly simple. However, you can tell in an instant that it is a masterpiece.

Nagai’s Tanka “The sunflower of Andalusia” uses a refrain, while Ikuya’s Haiku “Late afternoon” makes extensive use of the Japanese sounds “hi” and “ho (po)” that start with the “Ha” row. Both works are pleasant to the palate, but there is a crucial difference. “Late afternoon” evokes a visual “image” in the reader’s mind. The reader can picture a single Japanese bindweed flower blooming in a land called Portugal. Ikuya’s Haiku is not the only one that creates such a visual “image.” Most famous Haiku do this.

Haiku poems such as “An old pond, a frog jumps in, the sound of the water” by Matsuo Basho and “Rape blossoms, the moon in the east, the sun in the west” by Yosa Buson also easily form an image in the reader’s mind. The same goes for Masaoka Shiki’s “When I eat a persimmon, the bell rings at Horyuji Temple.” Excellent Haiku often form a clear image. There is a reason for this.

Haiku is not ego-conscious literature that expresses “This is what I think, this is what I feel.” Ultimately, it is non-ego-conscious literature that expresses the “harmonious and cyclical worldview” that underlies Japanese culture. It is a worldview held by Japanese people, who are said to be non-religious, that is so strong that it can be called a religion. However, this “harmonious and cyclical worldview” cannot be expressed through conscious effort. That is what it means when we say that Haiku is non-ego-conscious literature. Great Haiku poems can be “born,” but they cannot be “produced” consciously. This is why Masaoka Shiki encouraged “sketching (Shiyasei)”, saying, “Turn any scenery or object that catches your eye into a Haiku.”

Haiku is a sketch of the “harmonious and cyclical Japanese worldview” that exists a priori. It doesn’t work if you try to do it consciously. However, the writer’s consciousness can enter the unconscious realm and suddenly overlap with the unconscious worldview known as Haiku. This always becomes a linguistic image of a “harmonious and cyclical Japanese worldview”. When this happens, the Haiku becomes immobile, like a good landscape painting.

For example, if you compare Shiga Kaishi’s Haiku “Datusai-ki (Datusai -ki is a seasonal word for the anniversary of Masaoka Shiki’s death) Meiji is far away” with Nakamura Kusatao’s “Falling snow and Meiji is far away,” the difference is clear. Kaishi’s ” Datusai -ki ” was written first, but as soon as Kusatao changed the first line to “Falling snow,” this Haiku poem hit the target. The level of expression changed drastically. Aside from criticism that it is plagiarism, these two lines show the frightening nature of Haiku.

The reason why I chose Ikya’s haiku “Late afternoon” for comparison is because Nagai’s “The sunflower of Andalusia” poem clearly show that haiku are “images” while Tanka are “tunes”. Tanka are fixed-form poems of 5/7/5/7/7, but the “The sunflower of Andalusia” break the rhythm of 5/7/5/5/10. But no one cares. The “tunes” that can only be expressed in Tanka appeals strongly to the reader.

This is not typical of literary criticism, “The sunflower of Andalusia” poem shakes the strings of the reader’s heart. The strings of the reader’s heart shake and resonate with the poem of “The sunflower of Andalusia”. It is taboo to bring up something as vague as the heart in literary criticism, but that is the only way to describe it.

While a good Haiku has a clear image, the essence of a good Tanka is a tune that moves people’s hearts. Just as Ki no Tsurayuki wrote in the kana preface of the “Kokinshu”, “It is Tanka that can move the heavens and the earth without force, make invisible demons feel pity, soothe the hearts of men, and comfort the hearts of violent people.” “The sunflower of Andalusia” expressed the fundamental power of Tanka in the simplest form. The essence of Tanka is “tune”. The identity of Tanka will not change no matter what. If it had not been twentieth-century Tanka that had passed through the era of silent reading and written avant-garde tanka, it would not have been possible to express the original image of Tanka so simply and clearly.

I picked up a comb at dusk. the comb at dusk was just picked up by me

“Nayotake Shuui”

A pitiful and quiet Oriental spring: petals flow through Galileo’s telescope

“The Mysterious Musical Instrument”

It’s good to live with a man who comes home with the autumn sun in his bag

“Mozart’s Telephone Directory”

When life feels lonely, you hear the sound of water leaking somewhere in this world

“Temari Uta”

There are nights when I sleep with the radio on so that I won’t wander away from this world,

“I want a small violin”

The world of literature is cruel. There is no winning or losing, but only those who leave behind outstanding works remain in people’s memories. Among Nagai’s tanka, the poem “The sunflower of Andalusia” stands out. From the height of this poem, the excellent Tanka she left behind can be interpreted in various ways. No one cares whether it is colloquial or literary. This is because a masterpiece is an outrageous expression that ultimately comes back to the work itself.

Yuji Tsuruyama

■ 金魚屋 BOOK SHOP ■

■ 金魚屋 BOOK Café ■