In 2024, both the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Artizon Museum in Tokyo are holding exhibitions of works by Constantin Brancusi. Celebrated for his pursuit of the essence in sculpture through simplicity and abstraction, Brancusi is often regarded as “the father of modern sculpture.” But what is the appeal of his works? What makes us look at them from all angles for minutes on end? And why do they stay with us, reemerging from our memory long after we first encountered them? At a time when his works are gathering attention, I’d like to attempt to answer these questions, albeit in the very subjective manner that only the essay form allows.

Born into a family of farmers on February 19, 1876, in the Romanian village of Hobita, Gorj County, Brancusi showed a talent for wood carving from an early age. After attending the School of Arts and Crafts in Craiova, in the southern region of Romania, he entered the Bucharest College of Fine Arts, from which he successfully graduated in 1902. To pursue a career as a sculptor, he decided to continue his studies in Paris. After traveling to France mostly on foot, with prolonged stops in Vienna and Munich, Brancusi entered the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in 1905, joining the studio of Antonin Mercié, where he worked until graduating in 1906. In 1907, he opened his own studio near Montparnasse.

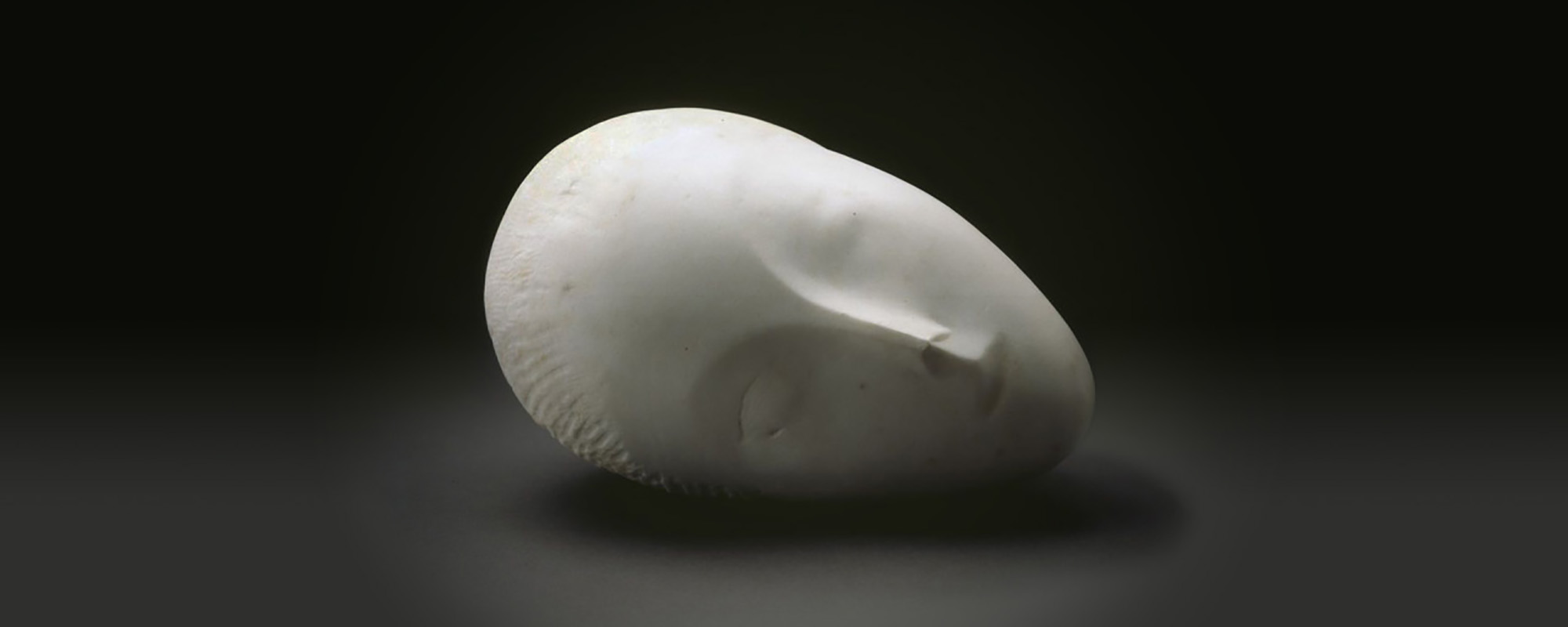

Even when casting became popular and widely used in sculpture, Brancusi chose to concentrate on the technique of carving materials. Works such as the Sleeping Muse, The Kiss, the Miss Pogany series, Maiastra, which is based on a mysterious bird from Romanian fairy tales, as well as the Bird in Space and Fish series, attracted attention from an early stage and were added to art collections around the world.

The essence that Brancusi sought to visualize by carving stone and wood was not the surface appearance of things but rather the “actions” that represented them such as flight or singing for birds, and swimming for fish. He aimed to express through sculpture the “inner nature” of living things, which had not been the focus of sculpture until then.

The Infinity Column (Targu Jiu, Romania)

The Table of Silence, The Gate of the Kiss, and the Infinity Column, which can be seen in the park in the center of Targu Jiu City, might be the most familiar works to Romanians. This series of works was completed in 1938 as a memorial to the soldiers who died defending the area around the Jiu River during World War I. While drawing on Brancusi’s signature style, this ensemble is characterized by the continuity of death and eternal life, a motif often seen in Romanian folk crafts. Since ancient times, Romanians have felt a special attachment to the archetype known as the Tree of Life, which is firmly rooted in the earth and stretches endlessly into the sky. Brancusi’s Infinity Column is thought to embody this archetypal motif.

In Japan, Brancusi’s works can be seen in permanent exhibitions at the Artizon Museum (the former Bridgestone Museum of Art) and the Yokohama Museum of Art. I learned that Brancusi’s work was in the Bridgestone Museum of Art’s collection when I happened to be visiting the museum a few years ago. There was a white stone sculpture in the middle of the exhibition room, surrounded by European paintings from the early 20th century. It was The Kiss, created between 1907 and 1910.

The Kiss (Artizon Musem Collection)

In this work, the faces of two people are carved from a single stone. They are one while being two, with their eyes and lips fused into one. The playfulness and simplicity of this work gave me an unexpected feeling of nostalgia. When I saw Brancusi’s The Kiss, which I had only seen in photographs, for the first time, I was reminded of the Gate of the Kiss, which I first saw during a family trip to Targu Jiu when I was a child.

At that time, I couldn’t understand why the triumphal arch-shaped monument that stood in the middle of the park was called “The Gate of the Kiss.” I asked my parents what was meant by the title, but either they didn’t know themselves or hesitated to explain it to a child, and I didn’t learn the answer. However, when I saw the stone carving The Kiss at the Bridgestone Museum of Art, I finally solved the mystery of the gate monument that I had seen as a child. The characteristics of the Kiss had been directly projected onto the shape of the Arc de Triomphe to represent the victory of life over death.

The Gate of the Kiss (Targu Jiu, Romania)

My encounter with Brancusi’s work at an art museum in Tokyo left a deep impression, not because Brancusi’s works are in art collections in Japan, nor because his sculptures were exhibited alongside works by painters like Monet, Cézanne, and Klee. After all, Brancusi lived and worked in Paris from 1905 until he died in 1957, where he interacted with many luminaries of the time.

What surprised me was that, surrounded by paintings by Monet and Klee, there was this “stone” in the exhibition room that reminded me of “home.” Brancusi’s works, which exude the aura of simplicity and warmth of Romanian crafts, felt familiar and nostalgic. Whenever I felt homesick, I would come to look at this stone and feel refreshed by its candor.

However, I would argue that the “home” that Brancusi’s works evoke has a dimension that transcends the individual and extends to humanity as a whole. His works, which bring natural peace and joy to people’s hearts, suggest a kind of origin, the “home” and the “roots” of all humans born on earth. To grasp the meaning of Brancusi’s works, viewers need to revive within themselves the memory of humanity, or rather the memory of the entire universe, encompassing both living and non-living forms.

I later learned that another connection between Brancusi and Japan was the sculptor Isamu Noguchi. Brancusi had a total of 15 assistants in his studio during his lifetime. Fourteen of them were from Romania, like Brancusi. The only person who was not Romanian was Isamu Noguchi.

Noguchi encountered Brancusi’s works for the first time at the New York exhibition held in 1926 and wrote in his diary (“Isamu Noguchi, a sculptor’s world”) that he was inspired by Brancusi’s vision. The following year, Noguchi received a scholarship to study in Paris, where he was introduced to Brancusi and began working in his atelier. Brancusi could not speak English, and Noguchi only spoke broken French, so their communication was not through words but through their eyes, gestures, materials, and movements. According to Noguchi’s diary, Brancusi, as his master, demanded concentration from his assistants above all else. His focus on work and his obsession with how to use tools may have reminded Noguchi of the spirit of Japanese artisans.

Bird in Space (Yokohama Museum of Art)

Brancusi’s works are loved worldwide because they speak to us through archetypes and universal symbols, expressing something fundamental about humanity. The work “Bird in Space” in the Yokohama Museum of Art’s collection is a good example. This series was created based on the idea that the essence of birds is flight, but it also embodies humanity’s dream of reaching great heights. Brancusi’s decision to use hard materials like bronze and stone to express flight, song, and soaring to the sky is also intriguing. We can see it as an attempt to breathe life into non-living objects.

There is a famous episode about “Bird in Space.” The work was first mailed to the United States in the 1920s for the exhibition in New York, but import customs did not treat it as a work of art and almost taxed it as a tool. We can interpret this as understandable if we consider that those were the early stages of modern sculpture. On the other hand, not being able to recognize “flight,” “bird,” or “soaring to the sky” when you see them could be a sign of decay, of a crisis unfolding within our humanity.

One hundred years on, are we doing better at recognizing “flight” or “song” or “love” when we see them? Overwhelmed by distractions as we now are, we might actually be on the brink of losing even the capacity to truly “look at” other humans, art, and the world around us. This new crisis may have been the incentive to bring Brancusi’s work into the spotlight in France and Japan at the same time. His works intrigue us with their familiarity, pointing “home” and keeping our gaze focused until we grasp their playfulness and the essence they convey.

Perhaps the only way to reverse the process of losing our humanity is to trace the memories of the universe that are preserved in our human DNA. The ability to look at things and grasp their essence, to understand what they truly are, is connected to something that we humans share with the birds, the fish, and the stones. With their simple, primitive forms, Brancusi’s works invite us to refine our perspective by going back to the basics and looking at the world with the eyes of the heart.

Ramona Taranu

*Pictures of the Infinity Column, The Gate of the Kiss, and The Table of Silence can be viewed on the homepage of Centrul Brancusi.

*This essay was originally published in Japanese on February 17, 2016. The introduction of the English translation was edited and adapted to reflect relevant events from 2024.

■ 金魚屋 BOOK SHOP ■

■ 金魚屋 BOOK Café ■