Introduction (2)

After the Second World War, Takeo Kuwabara published “Haiku as the Second Art” in which he severely criticized haiku. As the term “second art” suggests, Kuwabara considered Western self-conscious literature, which expresses the unique thoughts and feelings of the author, such as free verse, novels, and plays that became mainstream in Japanese literature after the Meiji Restoration, to be the “first art.” It is essentially world standard literature.

Compared to this ego-conscious literature, haiku has many heterogeneous elements. In principle, haiku is a fixed-form literature consisting of a 5-7-5 syllable stanza and a seasonal word. By incorporating seasonal words into a short number of characters, it inevitably becomes a realistic depiction of scenery. Haiku poets will say that they are all different, but when viewed from a broader perspective, they produce a large number of similar poems. It is not uncommon for a haiku poet to compose 10,000 or 20,000 poems in a lifetime. However, such a large number of works is in itself impossible in ego-conscious literature. Haiku is literature created by form.

The same can be said about societies and haiku meetings. What is necessary for ego-conscious literature is constant self-questioning. Even if one privately studies under a certain author, there is no need for societies, nor for mutual criticism in haiku meetings.

So how did haiku poets react to Kuwabara’s “Haiku as the Second Art”? A typical example is once again Takahama Kyoshi. Kyoshi said, “It can’t be helped if haiku is a second art or a third art.. The nature of haiku cannot be changed.” He was defiant, not caring at all about second- or third-rate literature. However, the idea that “the nature of haiku cannot be changed” is an intuitive truth.

Modern and contemporary people after the Meiji Restoration, that is, we, define literature as Western ego-conscious literature. There is no other definition of literature. In fact, works by Matsuo Basho and Yosa Buson from the Edo period are interpreted and evaluated according to the modern definition of literature. Everyone argues that in the end, it is the author’s own expression. The myth of a genius with an outstanding individuality prevails. However, Basho’s ” An old pond and the sound of a frog jumping into the water ” and Buson’s ” The rape blossoms and the moon in the east and the sun in the west ” as well as Shiki’s representative Meiji poem ” If you eat a persimmon, the bell will ring at Horyuji Temple ” do not express the author’s thoughts or feelings at all. They are purely objective descriptive poems, extremely simple descriptions of scenery. Ultimately, they are anonymous poems that anyone could have written. Their literary quality cannot be revealed by the method of criticism of ego-conscious literature.

The aporia of haiku begins here. It was the poets of the avant-garde haiku movement who took on this aporia head-on. It began with TomizawKakio, was continued by Takayanagi Shigenobu, and ended with Kato Ikya and Yasui Koji. Even now, there are poets who write the multi-line haiku that is synonymous with Shigenobu. There are also a fair number of writers who dislike traditional haiku, are independent of any association, and write avant-garde haiku in the style of Ikya and Koji. However, they are not the successors of avant-garde haiku. Multi-line haiku has already become a mere formality, just like haiku without a season or rhyme. The same can be said of the poets who write avant-garde-style haiku. The close struggle between the works and theories that was present in the avant-garde haiku movement has been lost. It is the habit of poets to simply follow the style of their outstanding predecessors.

By grasping Masaoka Shiki’s literature, Kyoshi intuitively came to the truth that “no matter how hard one tries, haiku is bound to be a descriptive expression, because of the fixed form of 5-7-5 syllables and seasonal words.” However, he did not explore haiku any further. He said that “haiku is national literature,” but there was no “definition of haiku.” He lowered the threshold further and further, believing that if one adheres to the fixed form of 5-7-5 syllables and seasonal words, one meets the minimum “literary requirements.” And the majority of haiku poets followed Kyoshi’s formal definition of haiku. This has brought about the secular fervor of haiku that continues to this day. If one follows the great master Kyoshi’s definition of haiku literature, even if it is criticized as a playful art, it can be ignored as it is all for the sake of sublime haiku literature. But that is a very Japanese laxism. If it is literature and has unique Japanese characteristics that cannot be captured by the modern definition of literature, then the principles of haiku must be rigorously elucidated.

Avant-garde haiku poets, so to speak, explored to the limit the subjective haiku that was advocated by Mizuhara Shuoushi and continued until Emerging haiku. They elevated haiku to the level of ego-conscious literature that could rival modern literature. However, it did not become literature of the same quality as modern literature. This is because haiku poets were fighting not against themselves or others (society), but ultimately against the haiku form. However, the true nature of the haiku form would not be revealed unless a strong sense of self was exercised.

The greatest achievement of avant-garde haiku is that it has not added or subtracted from the fixed haiku form as in previous avant-garde attempts, but has explored the principles of haiku form and clarified the way to gain freedom within the fixed form. The principle of haiku is 5-7-5 syllables and a seasonal word, and this will not change in the future. No one can change that. However, if you accurately grasp the principles of what haiku is trying to express with 5-7-5 syllables and a seasonal word form, it is possible to express freely.

I marched to the battlefield, marched to the battlefield

It’s like mud stuck to my retina

A snake runs through my war-torn eyes

The moon rises on a single tree of despair

TomizawKakio, the Emerging haiku poet and a founding father of avant-garde haiku, was born in Ehime Prefecture in 1902 (Meiji 35). Many young men born from the end of the Meiji period through the Taisho period were conscripted, but Kakio was sent to fight in Central China in November 1937 (Showa 12) at the age of 36 (by Japanese age reckoning). The Second Sino-Japanese War, which began with the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, broke out on July 7, 1937, so he was called up in the middle of fierce fighting. He fought in various battlefields for about two and a half years until he was discharged in May 1940 (Showa 15) after contracting malaria.

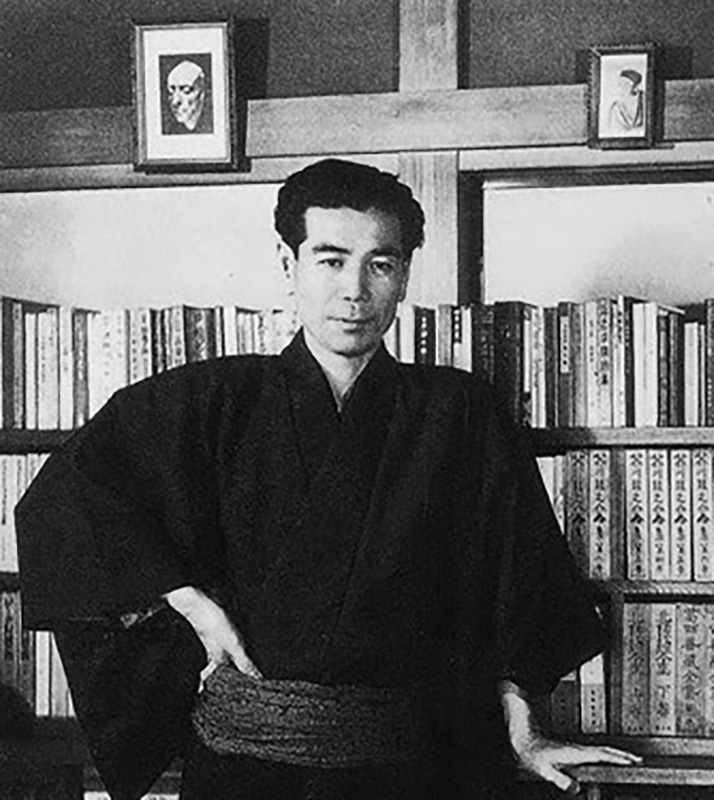

TomizawKakio

Poems such as ” I marched to the battlefield, marched to the battlefield ” were written on the battlefield. They were published in “Kikan” magazine, edited by Hino Sojo, and included in his first collection of haiku, “Heaven’s Wolf.” “Kikan” is a magazine of the Emerging haiku, on a par with “Kyoto University Haiku magazine.” Reading his poems, it becomes clear that Kakio experienced the horrific battles. However, they are not straightforward criticisms of war, like Inoue Hakubunji’s “I lecture, struck by the sound of military boots” or Saito Sanki’s “A red flower blooms between my eyebrows, a machine gun.” Kakio’s haikus are objective descriptions of the horrors of war, and express the exhaustion and despair of the mind and body through internalized scenes.

In February 1940 (Showa 15), when Kakio was released from conscription, Hirabayashi Seito, Inoue Hakubunji and others were arrested on suspicion of violating the Peace Preservation Law. This was the first crackdown on Emerging haiku. The crackdown came to an end in August of the same year when Saito Sanki, who was writing anti-war poems most vigorously, was arrested. However, Kakio was spared the consequences. Although the original words were replaced with more moderate ones, “Heaven’s Wolf” was not stopped by censorship and was published the following year in 1941 (Showa 16). This may have been influenced by the fact that many of the arrested haiku poets were behind the lines, while Kakio had served in the war. The fact that Kakio’s poems were not explicitly anti-war may also have been a reason for his escape from crackdown.

Kyoshi was convinced that haiku was “flowers, birds, wind, and moon.” He categorically stated that it was nothing more and nothing less than flowers, birds, wind, and moon. Immediately after the Great Kanto Earthquake, he said, “An earthquake is unlikely to become a haiku,” and “Perhaps war is not a suitable subject for haiku,” and in fact wrote no haiku about the earthquake or war. Kyoshi was close to resigning himself to the idea that haiku is not a vessel for expressing human self-awareness. That is correct. So what about Kakio?

A butterfly falls, a loud noise of the freezing period

Camellias scatter in the air, a lukewarm midday fire

The red creature moves to cross the strait

These poems were written while Kakio was recovering from malaria after his first release from conscription, and were written during the height of the government’s crackdown on Emerging haiku.

It goes without saying that ” A butterfly falls, a loud noise of the freezing period ” is a work that clearly depicts the social climate of the time when the Pacific War was about to begin. It can be read as an excellent one-line poem on a par with Anzai Fuyuei’s “A lone butterfly crossed the Tartary Straits” (Spring) and Kitagawa Fuyuhiko’s “It has a naval base inside” (Horse). Of course, ” Camellias scatter in the air, a lukewarm midday fire ” and ” The red creature moves to cross the strait ” also verbalize the anxious social climate. However, they are not poems that directly express Kakio’s self-consciousness. To put it bluntly, these poems remain within the “framework of flowers, birds, wind, and moon” that Kyoshi spoke of. This is what makes Kakio’s poems stand out among the many Emerging haiku. Such poems do not come about by chance. There is a strong philosophy behind Kakio.

The term “essence of haiku” is often mentioned. Using this term carelessly can cause confusion.

The essence of haiku is, of course, the same as the essence of literature. Haiku, poetry, and novels should be a single core that runs through literature in general.

Each literature genre is its own genre in its own characteristics. Essence is essence, not characteristics.

This is where some people start saying that the essence of haiku lies in the seasonal theme and seasonal words. This is where things get even more complicated.

Tomizawa Kkakio “Rooster Diary”

Although there are few, Kakio has written excellent poetic theories. His thinking is fundamental. 99.9% of haiku poets stop at the idea that the essence of haiku is “the presence of seasonal themes and seasonal words.” They don’t try to explore anything beyond that. However, Kakio argues that “seasonal words and seasonal themes” are merely “characteristics” that distinguish haiku from other literary genres. So what is the “essence” of haiku?

Poetry seeks completion, yet at the same time continues to reject it — this fundamental contradiction is what draws us to poetry.

There is no such thing as a “conclusion” in poetry, only an “inevitable process.”

“Purity” is perhaps the form of something that rejects “meaning” and creates “new meaning” from it.

A poet has no choice but to live with the fervent desire to transcend his own limitations through his own poetry.

Aren’t poets, in the end, nothing more than eternal experimenters?

The space that poetry possesses is always a space that is extremely filled with poetry — I think of the weight carried by the unwritten part of a poem.

Aiming for haiku that goes beyond haiku..

TomizawKakio “The Tongue of Chronos”

Kakio uses the words “poetry” and “poet” in the context of free verse, a new genre added to Japanese literature after the Meiji Restoration. Free verse is a literary genre that began with the translation of Western poetry. Just as classical Chinese poetry up until the Edo period was a gateway for the inflow of cutting-edge Chinese culture, after the Meiji Restoration free verse became a receptacle for the inflow and acceptance of the latest Western culture. It goes without saying that it is a literature of self-awareness. Furthermore, Japanese free verse has consistently played an avant-garde role in Japanese literature. Kakio has a precise understanding of the characteristics of free verse, as can be seen from statements such as ” Poetry seeks completion, yet at the same time continues to reject it ” and ” Aren’t poets, in the end, nothing more than eternal experimenters?”

This attitude of incorporating free verse self-awareness and avant-gardeness into haiku is common to avant-garde haiku poets who came after Kakio, such as Takayanagi Shigenobu, Kato Ikuya, and Yasui Koji. It can be said that Kakio laid the foundation for this. In fact, Kakio, Ikuya, and Koji all composed free verse at one time. Although no free verse works by Shigenobu have been confirmed, it is well known that he interacted closely with poets in the magazine he essentially edited, “Haiku Hyoron”. Furthermore, approaching free verse was necessary in order to confirm “what poetry is.”

Tanka is the womb of all Japanese literature. It established the five-seven rhythm, and gave birth to literary genres such as stories, Noh plays, and haiku. The most distinctive feature of tanka, which reached its pinnacle in court tanka, is the expression of self-consciousness, “This is what I think, this is how I feel.” However, the tanka of the “Manyoshu” and the post-“Shin Kokin Wakashū” poet Minamoto no Sanetomo are almost purely descriptive tanka.Tanka also served as a connecting base for free verse (new style poetry) during the Meiji period. Yosano Tekkan and Akiko’s “Myojo” gave birth to Kitahara Hakushu. Tanka has been writhing as the womb of Japanese literature to the present day, to a somewhat eerie extent. There is no unwritten rule that tanka is literature if it adheres to the fixed five-seven-five-seven-seven format. If it does not have outstanding characteristics in terms of content or form, it will not be recognized as a great poem. It is obvious.

In contrast, haiku, which was created by cutting out the 7-7 syllables and using the shortest possible format of 5-7-5, with the indispensable seasonal word, has an extremely narrow range of expression. Haiku exists to express the “cyclical and harmonious worldview” that is inherent in Japanese culture. This is represented by seasonal words – the changing of the seasons. This is why Kyoshi declared that “haiku is flowers, birds, wind, and moon.” If it follows Kyoshi like goldfish poop, then we must accept that much. However, on the other hand, the extremely narrow range of expressive possibilities in haiku gave rise to Kyoshi’s nonsense that “if it adheres to the fixed 5-7-5 and seasonal word format, it is fine literature.” His teacher, Masaoka Shiki, never said such a thing. In the world of haiku, excellent haiku do not become clear until 30 to 50 years have passed. This is because the average living haiku poets overestimate the haiku of the head of the society they belong to (their teacher) or their friends by making far-fetched connections that they call commentary. In no other genre is it more difficult to understand what poetry is and what makes good poetry than in the world of haiku.

There is no need to point out the haiku of Taneda Santoka or Hosai Ozaki to point out that excellent haiku do not need to follow the fixed five-seven-five syllable format with seasonal words. However, the poets of the no-season, no-rhyme school were empty-handed. Kakio sought the principles of poetry in free verse because free verse has absolutely no constraints in terms of form or content. An excellent poem comes into existence each time the author presents it as “a poem” and the reader recognizes it as “a poem and it is excellent.” This happens in an instant. Poetry is an intuitive, assertive expression, so an excellent poem can be recognized and acknowledged in an instant. Also, free verse, which has no form like tanka, makes it easier to grasp the principles of poetry. But of course haiku is formal literature, and Kakio wanted to be avant-garde within the form.

On top of the stone, the autumn demon is building a fire.

God’s wrath, God’s wrath, people have disappeared

The sky supported by a single dead tree

Lightning flashes, I must see clearly

The leaves shake, as the leaves shake, the tree feels uneasy

The stump reverberates with a rumbling sound

Kakio left behind only three collections of haiku. His second collection, “Snake’s Flute”, was published in 1951 (Showa 26). Some of his haiku express his wartime experiences and postwar society, such as “Aware this rubble city, a winter rainbow,” but many of his poems are increasingly abstract. There are also more poems expressing Kakio’s sense of self, but they do not express strong ideas or will. Rather, he aims for the disappearance of self-consciousness, as in “Lightning, I must see clearly.” This is well expressed in haiku such as “The leaves shake, as the leaves shake, the tree feels uneasy” and “The stump reverberates with a rumbling sound.”

There is no doubt that, as an Emerging haiku poet, Kakio was a writer who aimed for individualistic expression based on a strong sense of self. However, his individuality was not directed at criticizing society, but at expressing society as a whole through haiku. An early, cheerful piece such as ” A butterfly falls, a loud noise of the freezing period ” is a good example. However, in “The Snake’s Flute,” his expressions are clearly starting to become smaller. Kakio has reduced his sense of self and is trying to express the world by attaching himself to objects. What this self-consciousness attached to objects feels is anxiety. This is probably due to the influence of postwar society, which continues to expand in complex ways and is not so easily relativized. The anxiety felt by Kakio’s diluted sense of self, attached to objects, is also anxiety about whether he can fully express the world through haiku. In that sense, “The Snake’s Flute” is Kakio’s “collection of poems in crisis.”

Time, only two blades of grass are growing

Rain and smoke, or castle built on white sand

Silence – The burial of heaven begins now

The fate of stacking stones: bird fly horizontally

A snake crawls around, sinking the fire storehouse deep in the grass.

In the middle of the zero, standing on tiptoes and crying

His third and final collection of haiku, “Mokuji,” was published in 1961 (Showa 36). In January of that year, Kakio fell ill and was hospitalized, and he passed away on March 6th the following year (1962, Showa 37). Sensing that he was nearing death, Kakio called Shigenobu and asked him to publish “Mokuji.” As a result, it contains the fewest haiku out of the three collections. Also, if Kakio had lived longer, it is possible that it would have been published in a different form. However, “Mokuji” is an honest collection of haiku, and it clearly shows the avant-garde nature of Kakio’s haiku.

The title ” Mokuji ” suggests a double meaning, referring to the “Apocalypse” in the Bible – the Last Judgment and the Second Coming of Christ – and “Silence.” Kakio remained firmly within the haiku form and sought new avant-garde expressions. There is no sign that he was trying to destroy the haiku form. However, the more he sought avant-garde expressions within the haiku form, the more eccentric his poems became. Why? Because he knew haiku inside and out.

A new expression in haiku is ” castle built on white sand ” and an attempt to escape from the haiku form, to change it fundamentally, becomes ” The fate of stacking stones ” resulting in “bird fly horizontally.” They don’t fly high. However, the first haiku poet to put it into words was Kakio. If we limit ourselves to Kakio’s personal haiku work, ” In the middle of the zero, standing on tiptoes and crying ” would be his pinnacle and greatest work. It can be intuitively perceived as “excellent poetry,” but as a haiku, it is a dead end.

Figuratively speaking, Kakio descended to the “ecriture of zero” of haiku. Just as avant-garde dancer Hijikata Tatsumi tried to switch from avant-garde dance to a stylized dance like Noh in his later years, resigned to the idea that “the body cannot transcend experience,” Kakio’s haiku writing would have naturally required him to break away from zero if he had continued. Needless to say, Takayanagi Shigenobu took over that role.

Shigenobu chose the path of stylization, going from the zero point where Kakio had descended. However, Shigenobu was also a genuine haiku poet and knew haiku inside and out. Following Kakio’s “Apocalypse,” he tried to find a way to make the impossible possible through “Kuro – misa” — forbidden “black magic”.

Yuji Tsuruyama

■ 金魚屋 BOOK SHOP ■

■ 金魚屋 BOOK Café ■