Introduction

Avant-garde Haiku poet Yasui Koji passed away on January 14, 2022. In May of that year, I visited Yasui’s former residence with haiku poet Mr. Sakamaki Eiichiro, and the family kindly handed over Yasui’s manuscripts and documents to us. Mr. Sakamaki took home most of the books, and I took the manuscripts, but twenty cardboard boxes are still piled up in my small workroom. I have sorted through those manuscripts and am currently serializing “Yasui Koji Study.” Yasui was an astonishingly prolific writer. To publish a Collection of haiku book, he wrote several times as many haiku notes. The purpose of the Yasui Koji Study is to plainly introduce the details of Yasui’s haiku creation method in chronological order.

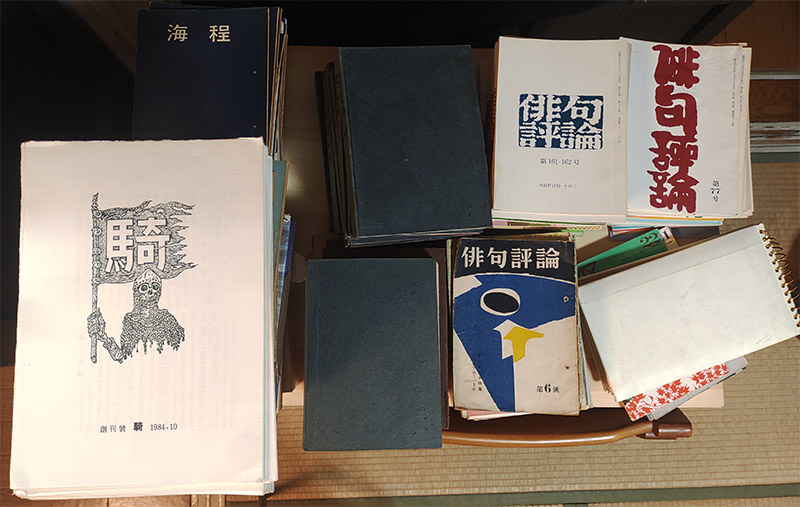

Apart from the manuscripts, I was also given some coterie magazines that Yasui had been involved in, because Mr. Sakamaki already had them and didn’t need them. These were magazines such as Haiku Hyoron, UNICORN, Riraza, Haiku Kenkyu, Kaitei, and Ki. Although not a complete set, they include magazines from the early days of avant-garde haiku right through to its heyday. This Serial Criticism “Takayanagi Shigenobu and His Etra” will analyze these magazines and reveal the history of avant-garde haiku. However, before starting the full-scale series, I would like to give an overview of ” What is avant-garde haiku?” and ” What is Haiku?”.

It goes without saying that Takayanagi Shigenobu was at the centre of “avant-garde haiku.” Of course, its seeds can be found in the Shinko haiku movement of the early Showa period. Tomizawa Kakio, whom Shigenobu looked up to as his mentor, was a representative writer of the Shinko haiku movement. However, this does not mean that Shinko haiku suddenly appeared. Its beginnings can be traced back to when Mizuhara Shuoushi left Takahama Kyoshi’s “Hototogisu.” Shuoushi left “Hototogisu” in 1931 (Showa 6).

Shuoushi advocated “subjective haiku” in opposition to Kyoshi’s “Hototogisu,” which was entirely devoted to “sketching.” Shuoushi criticized Kyoshi, saying, “Even if you despise subjectivity, cast away your heart and sketch objectively, what you see with your eyes is nothing more than the superficial beauty of nature…. Simply pursuing the truth of nature does not qualify you to be a poet. What you see through your subjective eye and cultivate your heart is the literary truth, and one who respects this is a poet”.

The power of the Hototogisu at the time was immense, and Shuoushi’s rebellion became a major scandal in the haiku world. Such was Kyoshi’s power that it was unthinkable to go against the Hototogisu; doing so would mean that one could not survive as a haiku poet. Kyoshi also openly put pressure on Shuoushi. In Kyoshi’s only historical novel, A Hateful Face, he likens himself to Oda Nobunaga and Shuoushi to Kurita Sakon, a military commander who rebelled against Nobunaga, writing, “Nobunaga gave the order: ‘Behead Sakon.'”

These kinds of power struggles and struggles for leadership are commonplace in the haiku world. They’re not as obvious as they once were, but they still exist secretly. It makes you angry when you are harassed, but if you think about it objectively, that’s just the kind of place the haiku world is. One of the purposes of this series is to calmly reveal why the haiku world is so worthless, and why its level is so shockingly low. The worthlessness of the haiku world will likely never change, so it’s best to think about haiku including that.

When the pear blossoms, the fields of Katsushika are cloudy

Katsushika and Momo no Magaki are also on the edge of rice paddies.

A child cutting rush grass and a little gebe running along the water

This is a representative haiku from Shuoushi’s first collection of haiku, Katsushika (1930). “Brilliant subjectivity must be the essence of a haiku,” Shuoushi wrote, but at first glance most readers will not understand where the subjectivity is expressed.

Shuoushi’s subjectivity is expressed through the active use of archaic words and phrases found in Tanka. Unlike Kyoshi, he does not simply sketch the scenery as it appears to his eyes, but first internalizes it and then expresses it. The use of archaic words and phrases was Shuoushi’s subjectivity. As a result, although the basis is sketching, the range of expression in haiku has been broadened slightly. There are still haiku poets who discuss the relationship between Shuoushi and Tanka, but this is not a big issue. Towards the later period, the influence of Tanka completely disappears from Shuoushi’s work. It was only a passing one.

Although Shuoushi proudly advocated subjective haiku, Kyoshi’s reaction was cold. It is well known that after reading Katsushika, Kyoshi harshly criticized it, saying, “Is that all there is to it?” Shuoushi’s haiku only changed slightly by internalizing the scenery. Shuoushi made a big show of leaving Hototogisu, but in the big picture he was still a sketchy poet. If we’re talking about a haiku poet who actively brought new terms and expressions to haiku, Yamaguchi Seishi, Shuoushi’s ally who later parted ways with him, is far greater.

However, Shuoushi’s subjective haiku later had an unexpected impact on the haiku world, giving rise to a new generation of haiku poets.

The sound of gunfire makes the birds, animals, fish and shellfish cold and cloudy

Saito Sanki

In the darkness, soldiers arrive one after another.

Katayama Toushi

War stood at the end of the corridor

Watanabe Hakusen

My lecture is hit by the sound of military boots

Inoue Hakubunji

Just going through the motions and quietly moving forward

Tomizawa Kakio

Many of the poets of the Shinko Haiku movement were members of the Kyoto University Haiku School, and so they are also known as the Kyoto University Haiku School. Shinko Haiku was at its most popular in the 1930s, but around this time Japan was heading down a path of fanatical militarism and national unity as it approached the Pacific War (World War II). The haiku quoted above are all blatant criticisms of the authorities. The authorities, who were tightening their grip on dissidents, could not have overlooked this, and from 1940 to 1943 many poets were arrested on suspicion of violating the Peace Preservation Law. This was the Shinko Haiku Suppression Incident (Kyoto University Haiku Incident). As a result, haiku’s open criticism of the current situation was dashed.

It is impossible to understand why the Shinko Haiku movement arose if one only looks at haiku. Kyoshi was cold towards Shuoushi’s “subjective haiku,” of course, but also towards the “new trend haiku” of Kawahigashi Hekigoto, who was once a close friend of Shiki’s scool, and the “seasonless, rhymed haiku” of Nakatsuka Ippekiro and Ogiwara Seisen-sui, which were born out of Hekigoto’s “new trend haiku.” He had concluded that it would not last.

It is foolish to try to forcefully attempt something new through the traditional poetry of haiku. … It is difficult to create a new form. Using old forms may seem easier, but in the end it is even more difficult. … It is not so easy to destroy it, even if you try to destroy it on your own. The hammer you use to destroy it will only bounce back against you. Haiku, our traditional poetry, is not so easy to destroy, no matter how much power you exert.

(Takahama Kyoshi, Taking Pride in the Theory of Flower and Bird Poetry, 1954)

Kyoshi’s consistent stance was that haiku must follow the “seasonal word in 5-7-5 format” no matter what is done, and that the basis is the realistic depiction of scenery and scenes from the real world. This is correct. The haiku format must absolutely be “seasonal word in 5-7-5 format,” and the basic method is “sketching.” This will not change in the future.

For example, the best of the Shinko Haiku works quoted above is Watanabe Hakusen’s ” War stood at the end of the corridor.” Why? Because it is a descriptive haiku. This haiku expresses the idea that “before I knew it, I could see war standing at the end of the corridor.” Whether or not to take this haiku as a criticism of war is up to the reader. It is true that Hakusen had feelings of dislike for the social climate moving towards war, but his best haiku are descriptive without explanation. To be precise, they are inner sketches. In that sense, it inherits Shuoushi’s “subjective haiku.”

Shinko haiku was the first in the history of haiku to feature socially critical poems, and because it was even more daring than Seishi in its incorporation of new words and phrases, it is still discussed as an important movement today. However, its greatest feature, social criticism, did not last. Even in the postwar era when society became more liberal and all kinds of speech was permitted, there were no Shinko haiku poets who actively wrote socially critical poems. This was not the case even for Akimoto Fujio (Higashi Kyozo), who was arrested under the Peace Preservation Law and served time in prison until the end of the war. Social criticism in haiku was also fleeting. In short, this was not the essence of haiku.

So why did Shinko Haiku emerge with Shuoushi’s “Subjective Haiku” as its starting point? Because it was a belated modernization of haiku. With the Meiji Restoration, Japan’s social and cultural norms changed from China to the West. Since the Kofun period, Japan had looked to China as its norm (modernity) to catch up with and surpass, but now it was the West. It was a major change that occurs once every 1,500 years, or rather a shock that turned the world upside down. In terms of culture, classical Chinese poetry, which had been a gateway to new Chinese ideas and terminology, was essentially wiped out, and free verse was forcibly created to import the latest Western ideas and terminology. Tanka, haiku, and novels also had to reexamine their respective foundations (identities). It was Masaoka Shiki who explored the principles of haiku and established them as a solid foundation.

In the early days, Shiki was passionate about creating new haiku along with Kyoshi and Hekigoto. However, through thorough research into Matsuo Basho and Yosa Buson, he made it clear that the basis (identity) of haiku is in the sketching of external scenery that is as free of ego-consciousness (subjectivity) as possible. Haiku is not ego-conscious literature that expresses “This is what I think, this is what I think.” It is non-ego-conscious literature that expresses the “cyclical and harmonious worldview” inherent in Japanese culture by combining two or three scenery (elements) from the world in a surprisingly simple and straightforward way. Kyoshi’s theory of sketching is nothing more than a dogmatic summary of Shiki’s fundamental definitions.

However, after the Meiji Restoration in Japan, Western ego-conscious literature quickly became the basis of literature. Literature was defined as highly original creations born from the ego-consciousness of a unique human being. This was the so-called “modern ego-conscious” literature typified by Natsume Soseki. Needless to say, this was in sharp contrast to the non-ego-conscious literature of haiku. However, haiku poets were indifferent to this until the early Showa period.

We may be useless people, but we have inherited the traditional tastes of our ancestors and are fond of the beauty of flowers, birds, the wind, and the moon. When the time comes when Japan, through the efforts of those engaged in useful academic endeavors, finally gains a foothold in the world, Japanese literature will surely also raise its head in the world’s literary circles. And when the time comes when Japan reaches its greatest height, people of other countries will surely start to pay special attention to what literature is uniquely Japanese. At that time, I think that a depressed face will emerge later in plays, novels and so on, and people will start to notice that there is such a thing as haiku about the beauty of flowers, birds, wind and the moon.

(Takahama Kyoshi, Flowers and Birds Fuei, 1928)

Haiku is the shortest form of poetry, so it cannot be compared to the brilliance of a novel or a drama. However, … I felt that if I were to “a depressed face,” I would be lowering my own value.

(Mizuhara Shuoushi, Takahama Kyoshi, 1952)

Although Kyoshi’s claims are dogmatic and he has copied Shiki’s haiku theory, what he says is mostly correct. Kyoshi says that when Japan continues to strive to catch up with and surpass the West, and finally stands shoulder to shoulder with them, the only truly original literature Japan can be proud of in the world will be haiku, which is a non-ego-conscious literature based on sketching and a fixed seasonal form. He is right. However, there was a deep despair in Kyoshi’s work. Kyoshi had big dreams for both his talent as a literary writer and for haiku. But they were crushed. When it came to haiku, no matter what he did he could not escape Shiki’s teachings. What makes Shuoushi different from Kyoshi is that he did not feel the same despair as Kyoshi.

Simply put, Shuoushi tried to elevate haiku to the level of self-conscious literature on a par with contemporary novels, free verse, and drama, by advocating and practicing “subjective haiku.” He could not stand Kyoshi’s self-deprecating expressions such as “a depressed face.” He wanted haiku to be an expression with infinite possibilities on a par with the literature that was reborn after the Meiji Restoration, such as novels, free verse, and drama.

Haiku poets who think like Shuoushi still appear periodically. They want to think of haiku as literature that is small in size but has infinite possibilities for expression. But that is a mistake. No matter how many new words or strange rhetoric you use, the expressive possibilities of haiku do not expand. It always returns to the simple expressions of five-seven-five and seasonal words. The reason why many haiku poets are disrespectful and have excessive expectations of haiku is because they only see and know haiku, and are unable to see haiku in the context of Japanese literature and world literature. It is nothing more than the nonsense of a frog in a well, brought about by an almost shocking laziness and lack of study. Haiku has been the garnish for literary sashimi since the Edo period, and that will not change in the future. If you feel humiliated, you should try a different genre of expression.

Just to add, haiku poets who learned to express their self-consciousness through Shuoushi’s “subjective haiku” quickly gave birth to Shinko haiku, which was suppressed by the authorities and brought an end to the movement, but that was not all. There were haiku poets who expressed doubts about Shinko haiku from its heyday. Representative haiku poets known as the “human-seeking school” include Kato Shuson, Ishida Hakyo, and Nakamura Kusatao. Shuson and Hakyo were disciples of Shuoushi, and Kusatao emerged from “Hototogisu.” They turned their backs on the social criticism of Shinko haiku, but sought to deepen subjectivity as a way of expressing the writer’s inner self.

The moderate realistic inner expression of this human-seeking school has become the mainstream of haiku today. There are almost no haiku poets who simply sketch the scenery they see, as in the days of Shiki and Kyoshi. Instead, they first internalize real scenery and then express it realistically. The human-seeking poet who maintained his influence the longest was Shuson. He is sometimes called the Shuson Mountain Range. As works of Hakyo and Kusatao are far more attractive, yet the bland and mediocre poems of Shuson have had more influence, which is a very haiku-like phenomenon. Haiku essentially dislikes the expression of the writer’s ego.

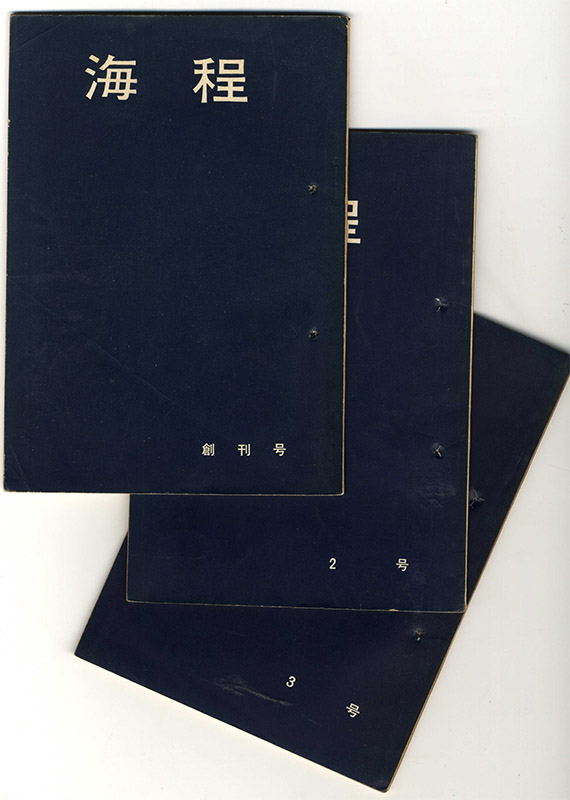

Furthermore, the influence of Shinko haiku, which had been crushed by the authorities’ repression, and its search for expression of self-consciousness continued after the war. This was the avant-garde haiku of Takayanagi Shigenobu and Kaneko Tota. Tota’s avant-garde haiku subtly inherited the social criticism of Shinko haiku. Tota also relaxed the fixed form of five-seven-five syllables and seasonal words, allowing for freer expression. As a result, Tota’s magazine “Kaitei” (a coterie magazine when it was first published, which later became a society magazine presided over by Tota) attracted many haiku poets. However, Tota’s “Kaitei” could only be said to be slightly avant-garde, and overall it was a traditional haiku society magazine.

Those who have seen the general meeting of “Kaitei” in Tota’s later years will know that at the top of the stage sat the great Tota himself, with all the editors of the “Kaitei” related magazines that were his own branch lined up below him. Whether big or small, having your own magazine is the pinnacle of a haiku poet’s career. The haiku poets of the “Kaitei” Friendship Society in the venue looked on with admiration and cheered. In short, just like Kyoshi’s “Hototogisu”, Tota also created a major force in the haiku world through his own efforts. It was admirable that he closed “Kaitei” before his death, but Seishi had also done the same (closing publication of his magazine “Tenro” before he died). I would say he was more admirable than Kyoshi.

Kyoshi was a man obsessed with his own interests and wealth. This is why the society magazine “Hototogisu” has remained a hereditary magazine to this day. It’s not like the arts and crafts taught in the hobbies of tea ceremony or flower arranging, and such a shameful thing would never happen in the world of literature. Yet it is done openly and no haiku poet says anything. This is because even today “Hototogisu” is a large society magazine and the heart of the haiku world. It’s reality, so there’s no point in criticizing it, but the point is that haiku is somewhere between literature and non-literary expression. In the haiku world, if you throw a stone, you’ll hit a “teacher.” Most of the time, these are teachers you’ve never heard of. Haiku is literally somewhere between literature and the arts and crafts taught in the hobbies.

Yuji Tsuruyama

■ 金魚屋 BOOK SHOP ■

■ 金魚屋 BOOK Café ■